by Michael Dhar

“Marketing” and “branding” sound like dirty words if you’re a scholar or an artist. I take that back — actual dirty words are awesome if you’re a scholar or an artist. “Marketing” and “branding” sound like compromised ideals if you’re a scholar or an artist, which is much worse than crudely referencing sex or taking the lord’s name in vain. (That just makes you a “cool professor.”)

They’re pretty uncomfortable words to most of us, but something we must generally accept — in the same way most people hate networking, yet still print up business cards. But those academics and artists who hold university positions can set themselves apart; academia is separate from — above, really — all of that. Which is why the resignation of Alice Dreger, in protest of Northwestern University privileging academic branding over academic freedom, must be celebrated as an act of courage and conscience.

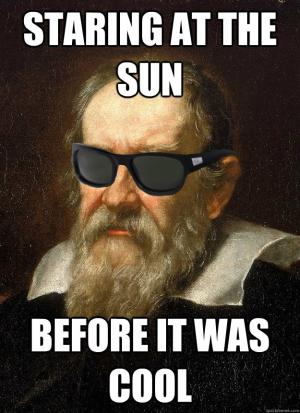

Anyway, that’s the press release I might have written were I Prof. Dreger’s publicist (or branding manager, say) . Of course, academia is not separate from marketing — universities must sell themselves, as well. They need brands to attract suckers (I mean, undergraduates). Academic researchers must sell their projects to get funding. Artists must contrive those horrible artist statements. And Alice Dreger’s very act of anti-branding is itself a brilliant act of branding. You see, Dreger has written a book on academic freedom and scientific controversies. Her resignation is priceless press, and it seals her brand as a warrior for intellectual independence. (The book is “Galileo’s Middle Finger” — she’s a cool professor — available now on Amazon!)

To be clear, I don’t suspect any underhanded dealings here — no invented outrage so that she could courageously resign and sell more books. The facts of the incident seem clear: Dreger, a medical humanities and bioethics professor (formerly) at Northwestern, guest-edited an issue of the university’s Atrium magazine, which included an essay about a consensual blowjob between a nurse and a patient. Northwestern said that essay violated the university’s “branding agreement” with the medical school, and had the issue taken down.

That act of censorship inspired the resignation of Dreger, who said, “Academic freedom is always going to cause brand problems. A brand is very much about something specific, and a university has to not be.”

Well, that’s great! It’s just pretty funny how all this rebellious, anti-branding activity bolsters Dreger’s personal brand so perfectly. This quote, from Greg Lukianoff of FIRE (Foundation for Individual Rights in Education), is just priceless:

“I am proud that Alice was willing to take this stand for free expression and academic freedom, and I strongly recommend her book, Galileo’s Middle Finger.”

I’m sure he means everything he says there. But I can also just see him holding up a copy of the book at the end of that quote, a big Coca-Cola smile on his face for the cameras.

Because rebellion, of course, is a brand, too. Just walk into any Hot Topic or review youth popular culture since forever (or, at least, the ’50s). Anti-branding is a brand, too. Just look at how well Adbusters and the like have sold the anti-corporate lifestyle.

Anyway, I would like to say fuck Northwestern (I’m a cool professor!) for their act of prudish censorship. But, concomitantly, congratulations to Prof. Dreger on the tremendous ad campaign that fell into her lap. She should be OK — as she has said, she was relatively free to resign her post, because she has income from the book and scheduled appearances. So hopefully that resignation will sell some books. More people need to read about Galileo, anyway.